Sketchnoting for Teaching, Learning & Listening

November 21, 2016

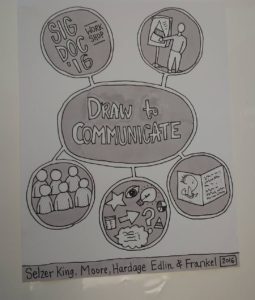

As many of you know, I’ve been working to develop a sketchnoting practice for a number of years. This practice of drawing or sketching has provided me with a good deal of structure both as a teacher and as a thinker, and I wanted to pause for a moment to demonstrate how/why this seems important. My colleague, Abigail Selzer King, and I worked with some students to present some of this work at SIGDOC. We provided a workbook, and we challenged participants to consider how drawing might help them solve problems.

But, of course, as we shared in our workshop, drawing has been solving teaching and thinking problems for us for years. I began sketching fairly modestly, after a number of instructive sessions with Pat Sullivan [dream mentor], who would often say: “Can you draw me a picture?” This makes sense, of course, because in Opening Spaces, she [I’m pretty confident this is her and not Porter] writes that pictures help her think. Turns out, they help me think too.

Sketching to Teach

I am hesitant to claim that I teach through sketching explicitly, but I definitely sketch to plan. The sketching helps in a number of ways: 1) it helps me show students the interconnectedness of content that otherwise gets presented linearly; 2) it helps students imagine and reimagine the way readings and course content might be synthesized, and 3) truth be told: it keeps my planning down to a minimum. I shared this advice with the Draw to Communicate workshop, and one participant reported that it had worked for him too: keeping yourself down to one page can be a dream.

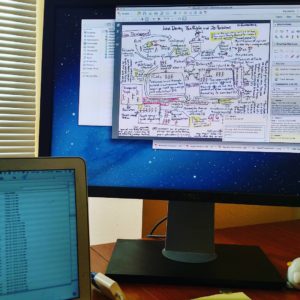

So, for example, my sketchnote for the Field Note process kept the class prep to one single page [yay!] and showed the rather linear process of how a field worker should be thinking about their research before, during, and after the process. This is much different, say than lesson on Weintraub’s theories of public and private, which you can view here: weintraub_krmsketchnote. My lesson on Weintraub relies on a modular page pattern, which organizes information much differently.

When I introduce students to the idea of sketchnoting, I most often do it through two major lessons: 1) the introduction of page patterns (post coming soon) and 2) the introduction of seed shapes (also coming soon). I argue, following Mike Rohde, that with 5 seed shapes (a dot, line, triangle, square, and circle), they can sketch anything they see. By arranging words and images in containers [boxes, circles, etc] and by organizing the page using dividers, students can listen and take notes without having to worry about the minutiae.

I argue to students that if they want to be able to understand the broad concepts, then they must necessarily let go of the tiny details and instead try to connect major themes and ideas.

Sketching to Think

Like my undergrads, my grad students have taken up sketchnoting as both a listening tool and a thinking tool. They borrow different page patterns and see if they can “think differently” about an idea or set of ideas with different page patterns. This is the same challenge I gave to myself when I first started investing in visual thinking. Having just picked up a Grids and Lines Architect’s book [by Princeton], I challenged myself to handle the ideas I was thinking with whatever page pattern came next. Doing so moved me outside of my way of thinking and into a new format for interacting.

New Approaches to Responses

Making Change in the Classroom: Some Practical Steps

November 12, 2015

I’ve been heartsick for years. I mean, it’s always sickening to consider the ways oppression and injustice runs throughout our judicial, education, and social systems in pernicious ways. But since the death of Mike Brown, a knot has settled under my sternum. I’ve long advocated for equality, and even as an undergraduate, I knew we needed to do more to redress inequalities. I directed For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide when the Rainbow was Enuf, as a first step. Working with this amazing text and the amazing women you see below, opened my heart and eyes and broke me. And I have continued to study the effects of rhetorics of oppression in the fields of technical communication and composition. So…maybe this heartsick thing is nothing new. But it feels new.

It’s not like I suddenly started caring about issues of oppression, but since August 2014, it’s been rough. I write about this as an academic and read about it more–that’s good practice for a junior scholar, I think. But recently, I can see that so many or at a loss for practical approaches to integrating change-making into the classroom. So, tentatively, I make these suggestions:

- Scour the sample studies, cases, and vignettes you use in your classroom. If they don’t sound diverse, do that. If your list of names looks like the line up from an all-white, all-male corporate function [David, John, George, Timothy, and Harold, for example], change it. Try: Maria, Juan, Jason, Jamal, Isla, etc. Paint a diverse cast for your classroom. I was a the Institute for Inclusive Excellence, and one of the speakers cited a study–which I’ve been searching and searching for–that says even this helps to defy stereotypes: non-whites, non-males exist in the world and they exist in our classrooms when we put them in our sample problems and cases.

- Take attendance through a “word of the day” that draws on current events or important historical facts/events. It takes 2 minutes to have students sign in and submit a word of the day–I did this to solve the problem of electronic attendance taking, but it works just as well with physical sign in sheets. Words of the Day I’ve used:

- Cultural Appropriation

- Manifest Destiny (Or stealing)

- Transphobia

- Misogyny

- Accidental Racism

- Gerrymandering

- DWB

- Supreme Court Justices: A Line Up

I don’t always use these kinds of culturally loaded and powerful terms. But I do sometimes. I also assign students to bring in words of the day that they don’ t know or understand, often from the local or current news.

- If you teach writing, teach through texts that raise critical questions about race, gender, sexuality, etc. Replace your John Dewey with other texts that introduce new perspectives. Recently, I’ve been using: the Ferguson Syllabus, Dworkin’s I Want A 24 Hour Period where there is No Rape, Black Girl Dangerous, Amy Schumer’s Friday Night Lights Parody, Alexander’s The New Jim Crow, Tuhiwai Smith’s Decolonizing Methodologies. But, of course, there are others. Share in the comments.

- Teach intercultural communication as a local phenomenon and assign students to explore places they’ve never been, where they know no one. I have this assignment if you want it. Feel free to email me k.moore [at] ttu [dot] edu.

There are more. But the first two are surprisingly easy. The other two take more work and thought, but where we have power, we can and should use that power to make some kind of change. If you’d like to talk about how to make changes in your classroom, I don’t have all the answers, but I will make time to talk to you, to think with you, to brainstorm, and to plan. Just email. Or, drop in to my online office hours on Skype [krm1881]. Or, join one of WomeninTechComm’s teaching talks.

This is just a start. But we have to begin somewhere.

Intercultural Communication…Not an Aside

August 24, 2015

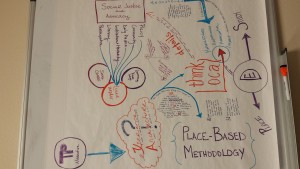

I recently had the pleasure of working with some Women in Technical Communication during a #teachingtalk on Intercultural Communication. The discussion, led by the ever-fabulous Lucia Dura, prompted us to consider our goals for intercultural communication. We worked to establish goals, means, and outcomes for a range of classes: Elizabeth and I, for example, are teaching service courses at our universities, where Tatiana and Jen are working on specifically Intercultural courses.

I learned a lot from working with these women, but here are some notable takeaways:

- Intercultural Communication is often treated as an aside or a specialty; we agreed that intercultural communication, ideally, should be integrated throughout professional writing/writing majors;

- Intercultural is more than just international or global; our students encounter intercultural situations regularly, but they might not identify them because instruction often privileges international rather than domestic interculturality.

- Notions of professionalism, which sometimes [if not often] motivate our PW courses, are wrapped up in culture and power, and if we allow professionalism to dominate our classes, we have a responsibility to communicate this transparently to our students;

- Intercultural Communication is difficult to teach because it is so wrapped up culture and power, so the means by which we assess adeptness in this area need to be concrete;

- One way to make the expectations concrete is to anchor the idea of intercultural communication in specific scenarios or specializations–this gives a site of application for the critical thought required of intercultural communicators.

This list is incomplete. And we all felt we needed more time to consider how to enact our goals for intercultural communication, but our next step is to develop some shared language, assignments, and assessment tools for integrating intercultural communication across curricula in PW/TC.

XA, Methodology, and Rhetoric

June 14, 2015

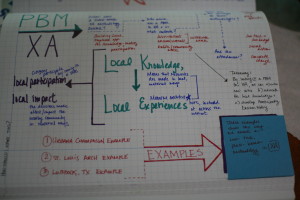

These past few weeks, I’ve been finishing up a writing project that discusses experience architecture (XA) in local communities. This project focuses on the ways that XAs can and should adopt decolonizing practices in order to ethically and justly construct XA projects and designs, particularly (though not exclusively) in local communities. This draws on some important decolonial work by Godwin Agboka and Linda Tuhiwai-Smith, Sullivan and Porter’s concept of praxis-based methodology, and Aunque Hommels’ notion of obduracy in cities.

I bought Hommels’ book several years ago and finally found a reason to read it for this project. If you’re interested in urban planning, I highly recommend it. He’s interesting, in particular for his really focused and useful definition of Actor Network Theory, which often gets danced around in rhetoric and technical communication as if it’s self evident (Potts (2013) is a notable exception). He writes that “actor-network theorists….describe technological development as a process in which more and more social and material elements become linked in a network. They investigate attempts by actors to stabilize that network. But the larger and more intricate a network becomes, the more difficult it will be to reverse its realilty. In this way, a slowly evolving order becomes irreversible” (Hommels, 2005, p. 27). In my chapter, I draw more specifically on two of Hommels’ frames for understanding cities as sociotechnical networks: embedded infrastructure and enduring traditions.

I worked from my ATTW Presentation and then, as usual, developed some maps to help me sort through my central ideas. The chapter is under review still, but once it’s forthcoming, I’ll share.

Why I Leave My Door Open

September 3, 2014

Since beginning my position as an Assistant Professor two years ago, I have been advised widely to SHUT MY DOOR. In fact, an Associate Professor once stopped in my [opened door] office to chastise me for having my door open. “Don’t you know you’ll never get any work done with that door open! SHUT IT!” I know, I know. In some ways, she was right: the more I leave my door open, the more likely someone is to come in and bother me. This is akin to the advice I was given to limit my time with graduate students to an hour per meeting or to create some really strict boundaries about how often I’d meet with them.

I GET IT. Really, I do: I’m not actually getting paid to meet with graduate students–and especially not undergraduate students, of all people. My job is to be a writer and a researcher. Now, when I realized that at the start of my first year, I was flummoxed. I felt like the wool had been pulled over my eyes. I realize that’s ridiculous: I have a wide range of mentors, and all of them prepared me in graduate school for reading and writing. But I had been so openly welcomed by my own professors, so reassured by their open doors and their willingness to take a minute to assuage fears that I couldn’t see a way into my role as a professor without the open door.

Despite this, I heeded this advice and spent a couple of semesters protecting my time by working off campus several days a week, ensuring that my students would schedule meetings with me if they wanted to see me. This left me feeling a bit empty and, frankly, I was less productive. I spent more time on email with students, trying to track them down–and less time actually understanding what they’d wanted/needed/were asking. It occurred to me recently that I had good reasons for leaving my door open–they’re just not necessarily in line with others’ “shut-your-door” assumptions. So, why do I leave my door open:

- I believe community is important in academic programs. Because knowledge production doesn’t happen in isolation, we need one another to think with and learn from. When professors scamper off to their own corners to write, it

- One way to build community is to be present. In fact, it’s rather difficult to build community without presence. We do it with our online students, but much of the community-building that happens at a distance develops with and from our 2 week residency program termed Mayinar.

- I learn from students when they come to my office. I learn about them: their values, their lives, their needs. This makes me a better teacher in the classroom. As importantly, I learn more about what they’re working on, expand my own ideas beyond my own ideas and readings. In academia, which can often be isolating, I find this important.

- It models work behavior for graduate students. No one tells graduate students how to work. People often [too often?] tell them what to do and/or give them a list of benchmarks to meet, but the daily work of accomplishing those tasks is left blackboxed. Although each scholar works in his or her own way, I think showing graduate students how and when you work is an important part of mentoring graduate students. There are certainly other strategies for teaching/sharing work patterns, but working in my office with my door open allows for students to walk in, say, “Are you busy?” And get a response like, “Yes. I’m working on a proposal for the next hour. Do you need something immediately or can we set up an appointment?” This kind of response 1) shows how work time is organized, 2) offers them a model for organizing time around writing, and 3) still demonstrates care and nurtures community through presence.

- I’m happier when I’m with people. I know this is hokey. I don’t care. I’m happier when colleagues and students are present. I’m better to myself, and I’m more clued in to the institutional workings.

So…I might change my mind on these things. But for now, I’m going to continue to work in my office with my door open.

CFP | Posthuman Praxis in Technical Communication

July 16, 2014

Call for Papers | Posthuman Praxis in Technical Communication

Things matter. And so do objects. In the past few decades, scholars across disciplines have developed theoretical frameworks like posthumanism (Hayles, 1999; Haraway, 1991), object-oriented rhetoric/ontology (Boyle & Barnett, 2014; Bryant, 2011), new materialism (Coole & Frost, 2010; Bennett, 2010), and Actor-Network Theory (Callon, 1999; Latour, 2007) to articulate and acknowledge the agency and importance of materiality and nonhuman actants. But relatively little work, with some important exceptions like Spinuzzi (2003), Knievel (2006), Graham (2009), and Potts (2014), has explored the implications of these theories for technical communication practice, research, and teaching. In their TCQ special issue on posthumanism, Mara and Hawk (2010) claim that envisioning technical communication as a posthuman practice opens up more possibilities for rhetorical action. We agree. As such, this collection follows Mara and Hawk in their broad definition of posthumanism as “a general category for the theories and methodologies that situate acts and texts in the complex interplays” among humans and nonhumans and that highlight the role of materiality in these interplays (3). But how exactly does attention to nonhuman, material agents shape, reconfigure, improve, and/or challenge our practice of technical communication?

This collection calls for studies that focus on technical communication practice informed by posthuman theories, broadly conceived. Becausepractice can dissolve the boundaries of terminology, we are less concerned with “camps” or theoretical allegiances and turn instead to research that demonstrates the implications of these theories for practice. Posthuman rhetorics are valuable for the field of technical communication not only as new ways of thinking but better ways of doing. It is with this practitioner ethic that we seek studies, researches, and projects revealing how attention to posthuman theories and methodologies have actually improved technical communication practice and have indeed opened up more rhetorical possibilities for those researching, teaching, and practicing technical communication. In other words, this collection is a call for studies ofposthuman praxis.

The editors welcome 500 word proposals that address, challenge, or respond to one or more of these questions:

- How has the shift towards posthuman theories shaped, changed, improved, or confounded the practice of technical communication? How do technical communicators practice differently given the recent attention to nonhuman actants and materiality?

- What research methods or methodological approaches most effectively integrate or incorporate posthuman theories? What kinds of studies specifically can illustrate the results of such methods and methodologies?

- What sites of technical communication practice require or benefit from attention to material systems or nonhuman agents? How might these benefits be articulated?

- How might current or common technical communication teaching practices be challenged by explicit attention to posthuman theories? How might collaborations, texts, and deliverables be re-examined in light of what these theories have to offer students?

In short, we are looking for ways in which attention to posthuman theories practically help technical communicators grapple with emergent agency in practice-based settings. This collection seeks contributors with a wide range of theoretical, pedagogical, disciplinary, methodological, and epistemological approaches. As such, proposed projects could:

- Offer original research, accounts, or studies of nonhuman actants in traditional sites of technical communication, like organizations, the public sphere, workplaces, or classrooms, or in interdisciplinary areas like health/medical communication, gaming and multimedia studies, environmental studies, or risk communication;

- Revisit, re-write or re-analyze an existing research project or data set in light of its non-human actants or new theoretical frames;

- Develop a theory of posthuman praxis that is grounded in practice or research.

The deadline for submissions is September 15, 2014. Decisions about proposals will be made by November 1, 2014. Final chapters will be expected by June 30, 2015. Please attach submissions as a Word file and email to Kristen R. Moore (k.moore@ttu.edu). Questions about the collection as a whole can be directed to either Daniel Richards (dprichar@odu.edu) or Kristen R. Moore (k.moore@ttu.edu).

Daniel Richards, Old Dominion University

Kristen R. Moore, Texas Tech University